"While at a banquet in New York City to receive the Ben Hogan award, Joe Lazaro sat next to comedian Bob Hope. During a light moment Hope invited Lazaro to play a round of golf with him sometime. Lazaro retorted quickly,” I'll be glad to play against you . . . how about meeting me on the first tee at midnight?”

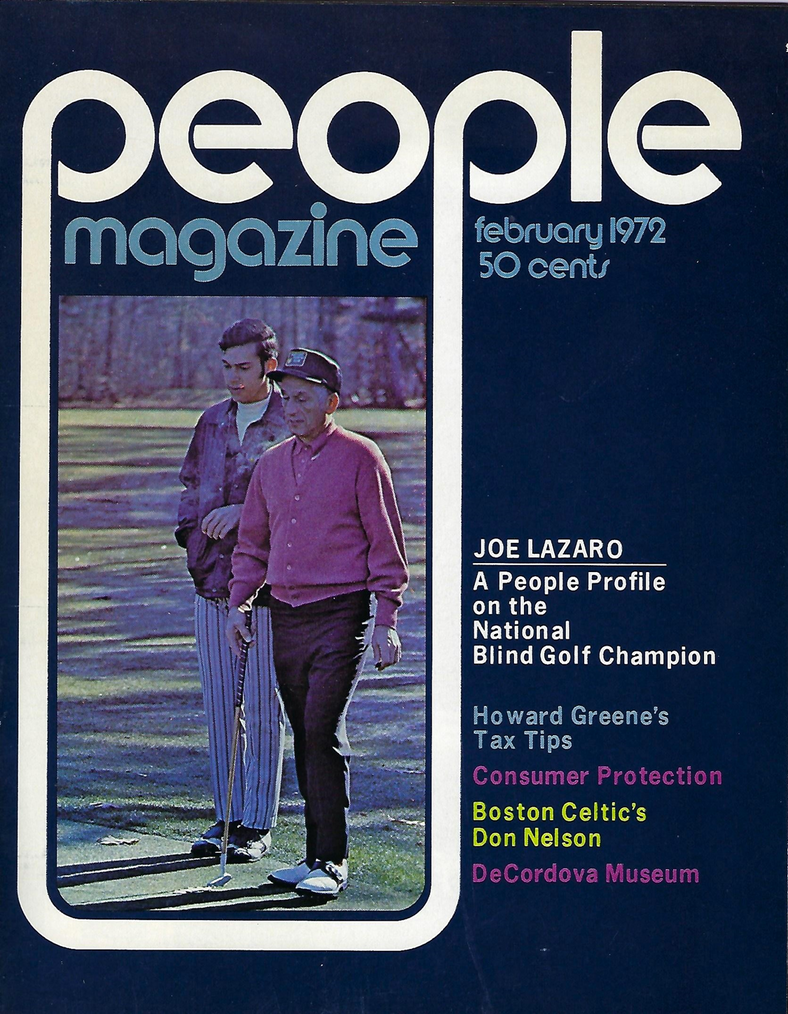

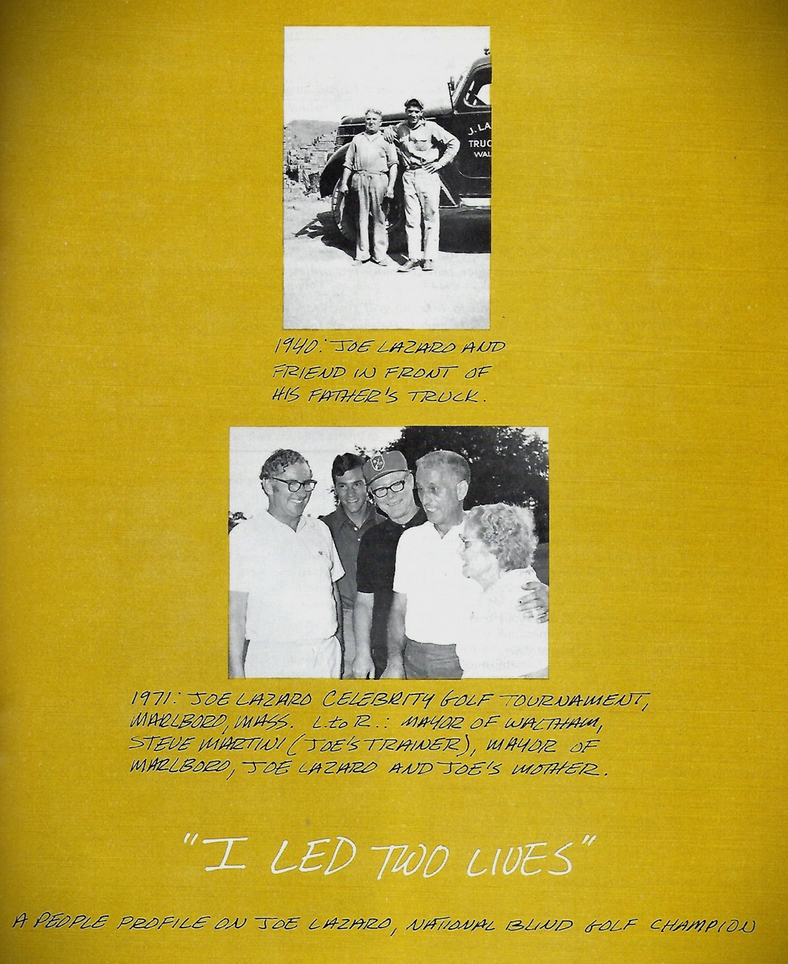

"Mr. Lazaro achieved national attention by annexing the National Blind Golf Championship in 1962 and, since then, he repeated as the country's top blind golfer in 1967, 1968, 1969, and 1971. This past summer the Waltham, Massachusetts Lions Club sponsored the First Annual Joe Lazaro Celebrity Golf Tournament at the Marlboro Country Club. Waltham Lions promoted the event in order to raise funds for the blind and the retarded-blind in the city. Mr. Lazaro gave all his support to the benefit and his mere presence attracted many sports celebrities to play in the one-day tourney.

"The amiable blind golfer has been an inspiration not only to the sightless but to all persons since national attention was beamed on him. The mere fact that so many pro athletes volunteered to play in the Lazaro Tourney this year attests to that.

"Ken `Hawk' Harrelson, who quit baseball to take up golf this year, was one of the many celebrities who made a special effort to play in the Lions tournament. He said of Joe, “He probably gives more effort than a professional athlete.”

"Almost two years ago Joe was named by the Golf Writers Association of America to receive the Hogan award for the golfer who best exemplifies the kind of courage Hogan displayed in coming back after his near-fatal auto accident."

Tommy Nevell, Waltham News Tribune 1972

Joe Lazaro is fifty-four years old and a life-long resident of Waltham, Massachusetts. He has a wife he calls "Skip", two daughters, Lynne who works as a stewardess for American Airlines and Joan, a secretary with Polaroid in Waltham. His fifteen-year-old son, Joey, attends Waltham Public Schools. Joe is employed by Raytheon's Waltham plant, where he dismantles defective radar tubes for salvage and reuse. In 1972 he will be celebrating his 25th year with Raytheon.

Joe has been playing blind golf for about twenty-five years, entering the National Tournament every year. In addition to the five National Championships, he has won two International Championships in Canada, his lowest score as a blind golfer being a 77.

An active man, Joe is a member of the Lions Club and has many public speaking engagements throughout the year. He loves to "bat the breeze" with friends, plays bridge, honeymoon whist, and poker (with braille cards). He recently joined Vincent's Health Spa in Waltham "to keep active in the winter months."

Born January 8, 1918, Joe went to local schools and played basketball and track. As a golf caddy at thirteen, he earned a dime per game and eventually worked his way up to a Class A Caddy at 80 cents per round. The following is a conversation with him on some of the important things that have happened in his life between his Class A caddy job and his current status as National Champion.

PEOPLE: Now that the readers generally know your background, let's talk about Joe Lazaro the person. Why don't you start with how you got into the service during World War II?

LAZARO: I was playing poker with some friends when it came over the radio that Pearl Harbor was bombed. I tried to enlist in the Seabees, but the waiting list was too long. I was drafted by the Army and I kind of enjoyed it. I was away from home for the first time; I learned how to depend more on myself for things. I was assigned as a truck driver with the combat engineers, also acting as a machine gunner and mine detector man.

PEOPLE: Joe, can you tell us about the day you lost your sight?

LAZARO: We were making a crossing in the Po Valley, which is in the northern part of Italy. My job at that time was to stand watch, while the mine detector team moved ahead. The team moved out into the mine field and a re-con jeep came by. The jeep was no more than fifteen feet between the team and me. This stands out quite vividly in my mind. I figured they were going up for supplies; it was just a secondary road. There were a few Italians in the area and as I was looking at this jeep, I saw this Italian peasant just behind the jeep. I can see him today as I saw him then, an old Italian man with an unshaven white beard, a short, vested jacket. This is the last thing I remember seeing.

PEOPLE: What kind of expression did he have on his face?

LAZARO: He had no expression, just a solemn Italian wondering what happened to his homeland.

I saw him just beyond the jeep. I can't say that I saw any explosion, I just felt it. The mine went off. It was the equivalent of fifteen pounds of what the Germans call tolite, which is similar to our dynamite. I felt the explosion and I knew I was hit and on the ground. I didn't lose consciousness.

" He has overcome his handicaps, by not only showing himself as a champion, but by being a pro."

Karen McCarthy - 7th grade Warren Junior High fan

I couldn't see. I felt an intense heat in my face and a splattering of, I guess it was, sand. I knew I wasn't shot, but I was on the ground, and something was wrong; I couldn't see. I kept hollering for Doc Hume, our medic. Doc Hume yelled back, "Don't worry, Joe, I'll be right back for you, you're all right." Physically I knew I didn't lose any limbs, but then I couldn't see.

PEOPLE: Were you mentally alert at the time?

LAZARO: I was mentally alert, but I was kicking and tossing my body around trying to make myself see. Doc Hume gave me a shot of morphine which didn't put me out, but I felt numb and didn't care what happened. I laid on the ground for what seemed like hours before the ambulance came.

PEOPLE: What happened to the rest of the squad that was with you?

LAZARO: The fellas in the jeep got killed; they hit the mine. The squad that was probing did come back. They were injured but not bad enough so they couldn't attend to me.

Newly married - Joe and his wife Skip, April 1946.

PEOPLE: At the time, did you think you would get your sight back?

LAZARO: I didn't know what the problem was, but I had bandages on my face and I knew that was why I couldn't see. I had an alibi. My buddy told me that I couldn't see because I had bandages on my face. I was satisfied with that answer. They took me to the evacuation hospital where I stayed overnight. The next morning, I went by ambulance to Naples.

PEOPLE: Did you know by the fact that you were going to Naples that what happened to you was serious?

LAZARO: I knew I was going to the general hospital to be cared for, but for what reason I didn't know. I remember being admitted and sensing a different atmosphere. It smelled like a hospital — ether and things like that.

PEOPLE: Did you ask the doctor what was wrong with you?

LAZARO: When the first doctor attended me, I asked him what the trouble was. He took off the bandages and put a flashlight in my right eye and asked me if I could see it. He put the flashlight to my left eye and asked me again. I said I could see a blotch of light. Right away, he started to talk in medical terms. He wanted to get another doctor for consultation. They consulted and brought me to the operating room, and when I got back, I had bandages on my eyes again. They treated me for seven days with medication and then took off the bandages. I knew I was by a window, but I couldn't see it. They put the flashlight to my eyes, but I could only see a blotch of light and only in my left eye. I asked the doctor, “What do you think?” He said, "It is too early to tell yet."

PEOPLE: Did you, at the time, think that you might get your sight back?

LAZARO: The doctor said, "You'll be all right. You will get your sight back as soon as we get you back to the States."

PEOPLE: How old were you, Joe?

LAZARO: I was twenty-six. It all happened so quick I didn't have time to think. I didn't start to think about it until I got back to the States.

PEOPLE: Did you know Skip, your wife, before the accident?

LAZARO: Yes, I met her in England. Our unit was taking our training there. Our squad went into town to a Fish 'n' Chips joint. As we walked in, we saw these cute kids sitting down. I'll tell you one thing, to be frank, the first thing I noticed about Skip was that she had a hell of a set of teeth. It was the way she smiled. She wore her hair in a pageboy with a little curl on top. And this was attractive to me.

PEOPLE: Did you tell Skip what was happening to you?

LAZARO: I thought an awful lot about it and I made up my mind to tell her the facts. So, I wrote her a letter and told her I had lost my sight. I didn't know if I would be totally blind. I told her that there was no sense in coming over here to the United States and marrying a blind guy because she could probably have her pick over there. She wrote back that it didn't make any difference to her; she was coming over anyway. This was like an injection in the arm, it gave me a big boost. She did come over. We were married two weeks after my discharge, on April 30, 1946. It's sort of a great feeling to know that there is somebody special to care for you. I think the biggest blow was around the twelfth or thirteenth month when the doctor finally came to me and said, "Joe, we have tried everything." I wasn't really shaky or shocked because they made sure that I was physically and mentally in good shape before they told me. I recall the morning he came in to tell me. He said, "Joe, I'm afraid you won't be able to see for the rest of your life."

PEOPLE: What were your first thoughts when the doctors told you this?

LAZARO: My first thoughts were, well, I was numb; I was speechless. I didn't say anything. The doctor just sort of walked off. He knew whether I would accept it or not from my reactions in the previous months. Then I really started thinking — what next? He came back to see me the next morning and said, "How do you feel?" I asked him twice, "Are you sure I'll be blind?" He said, "Yes."

PEOPLE: Did you get any sleep that night?

LAZARO: You don't really sleep. I mean, in a sense, sometimes when you can't see, you think you are sleeping and you are not. It's an odd way to put it. You don't see anything to begin with. You are trying to rest and even when you are sleeping, you are dreaming. You could be doing the same thing when you are awake, but you are sort of daydreaming. You have to accept it right away.

PEOPLE: When you finally did have a good night's sleep and you woke up in the morning, did you wake up some mornings feeling like a sighted person?

LAZARO: Yes, this happens to me even today. I will wake up in a semi-conscious state thinking I am a sighted person, but when I put my feet on the floor, I know. Sometimes, during the day when I get intensely involved in something, I feel this way. Sometimes I am so wrapped up in what I am doing, I make a quick movement and I may hit a post or something. It is the quick moves — you are not supposed to make quick moves.

PEOPLE: Do you create images when you are doing things?

LAZARO: Everything I do today, I visualize. I can make comparisons: Everything I saw before can be explained to me in a situation and I will understand. Let's say I am working on the car, putting on the muffler, which I can do. I know what they basically look like. To do this, you don't need sight. When you remove the old brackets, you know where the new ones go. People say, "How do you do it?" I visualize.

If you tell me what the Prudential Center looks like, I would compare it with the Empire State Building, which I have seen.

PEOPLE: What helped you to get through the first trying months. Were you a deeply religious person?

LAZARO: No, it is within yourself. It is just a mental effort. It is whether you accept being blind or not.

PEOPLE: Did the Army do a good job in rehabilitation for you?

LAZARO: They did a wonderful job. I wish I had paid attention and learned more. They helped me in all possible ways.

PEOPLE: Do your eyes get tired during the day when you are doing your job?

LAZARO: When you have lost your sight, your eyes do get tired just like anybody else.

PEOPLE: Do you watch television and what's your favorite program?

LAZARO: I get a lot out of television if they use a lot of dialogue. A variety show is too hard to follow, but something like a court case is good. One of my favorite programs is Dragnet because of the way they talk back and forth. Laugh-in is almost impossible to follow.

.

PEOPLE: How about the program called Longstreet?

LAZARO: (Laughter). I'm glad you asked that question. I think it's ridiculous! I think there is a lot of misrepresentation in that show. For instance, he will walk down an unfamiliar street, up a staircase, as if he knows exactly where everything is in the room. He projects the idea that he senses where everything is. This is fine for sighted people looking at the T.V. program, but it just doesn't work that easy. Don't misunderstand me; all of those things that he does can be done, but you have to probe a lot and he doesn't probe. He does things too conspicuously. To me the program is disappointing, but to a sighted person, I guess it's okay. It's like watching John Wayne in a World War II movie. He makes it look easy, but things are just not done that way.

PEOPLE: Would you play in the PGA?

LAZARO: This could not happen at the present because the PGA does not grant handicaps. However, if they changed their rules in the future, I would be interested.

PEOPLE: As a profession, if you had your choice, what would you like to do?

LAZARO: Basically, I like to be in the public eye. I have a deep feeling for people. They are exciting and make everything worthwhile. I would love to be a public relations man, especially dealing with the youth of today. I like to act like a sighted person.

LAZARO: I have good days and bad days, just like everybody else. Sometimes I am irritable and sometimes I am happy. Usually, I try to be happy and keep a healthy mental attitude. If you have the right mental attitude, you can find fun in whatever you do.

Joe Lazaro 1918 - 2013